As a young girl, I used to ride my bicycle down the road with her name on it. It was the main road around the Middletown Psychiatric Center where my mother worked and was named after the woman who spent her life working to make the lives of people with mental health issues and prisoners better.

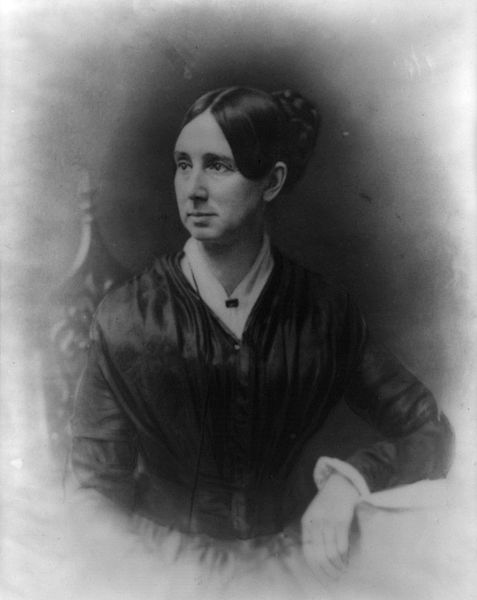

Dorothea Lynde Dix wore many hats. She was an author, a teacher, and a reformer. It was as a reformer that I first learned about her. It is as a reformer I continue to look up to her. The streets on the campus where my mom worked were named after people who had somehow tried to raise awareness to or helped reform the care people with mental health issues received in society. Her work changed people’s perceptions and her efforts kept them from being marginalized and forgotten by society.

Dorothea rarely spoke of her youth. She had a troubled background and her family was poor, but she used those experiences throughout her career to remain steadfast in her mission to help others.

Born in 1802 in Hampden, Maine, Dorothea faced many struggles every day of her life. Her father, Joseph, was an itinerant Methodist preacher and rarely home. Her mother suffered from debilitating depression. As the oldest of three children, Dorothea was left to care for the family most of her young life.

Though Joseph was an alcoholic and also suffered from depression, he taught her how to read and write. These skills were useful to Dorothea. Her lifelong love of books and learning came out of those years, which were often lonely and unpredictable.

Her wealthy grandmother in Boston took her in at age twelve and encouraged her to continue her interests in education.

That interest led Dorothea to establishing several schools in Boston and Worcester. She designed her own curriculum and taught in classrooms, beginning when she was still a teenager. She taught the wealthy in Boston, but she also taught the poor and neglected children out of her grandmother’s barn.

When her own health became poor, most likely due to depression, in the 1820s, she could not teach as often, so she started writing books. They were filled with ideas and morals to edify young minds. Though she had hoped to return to teaching full-time one day, her health was never good enough again to do so. She closed the last of her schools in 1836.

Her friends were so worried about her depression, they took her out of Boston and set sail on a sea trip to England. There she was inspired by British reformers and learned about new ways to treat those with mental health issues. She did return to teaching, but at an East Cambridge prison. The conditions were so terrible and the prisoners were treated so inhumanely, she decided things needed to be changed.

At the time, prisons were unregulated. Prisoners had no access to anything considered hygienic and violent criminals were housed with the mentally ill. Prisoners could be tortured in varying degrees by jailers whenever they felt like it.

Dorothea began to investigate by visiting every public and private facility that allowed her to enter. She documented what she found and presented her findings to the Massachusetts state legislature. She demanded these institutions be reformed.

Her reports—filled with dramatic accounts of prisoners flogged, starved, chained, physically and sexually abused by their keepers, and left naked and without heat or sanitation—shocked her audience and galvanized a movement to improve conditions for the imprisoned and insane.

State government funds were made available for the expansion of the state’s mental hospital in Worcester. Dorothea then set her sites on Rhode Island and New York before traveling around the country and then taking on Europe.

Dix traveled from New Hampshire to Louisiana, documenting the condition of the poor mentally ill, making reports to state legislatures, and working with committees to draft the enabling legislation and appropriations bills needed. In 1846, Dix traveled to Illinois to study mental illness. While there, she fell ill and spent the winter in Springfield recovering. She submitted a report to the January 1847 legislative session, which adopted legislation to establish Illinois’ first state mental hospital.

She was instrumental in the founding of the first public mental hospital in Pennsylvania, the Harrisburg State Hospital. In 1853, she established its library and reading room.

The high point of her work in Washington was the Bill for the Benefit of the Indigent Insane, legislation to set aside 12,225,000 acres (49,473 km2) of Federal land 10,000,000 acres (40,000 km2) to be used for the benefit of the mentally ill and the remainder for the “blind, deaf, and dumb”. Proceeds from its sale would be distributed to the states to build and maintain asylums. Dix’s land bill passed both houses of the United States Congress; but in 1854, President Franklin Pierce vetoed it, arguing that social welfare was the responsibility of the states.

Dorothea spent the U.S. Antebellum years traveling in Europe, with notable investigations in Scotland concerning reforms and meeting with Pope Puis IX in Rome.

One week after the Civil War began, Dorothea volunteered. She was appointed with outfitting and organizing the Union Army hospitals and overseeing all its nurses. She was the first woman to serve in such a high ranking role.

Dorothea was skilled at managing the flow of supplies and getting them where they needed to be, but she rarely got along with army officials or the volunteer nurses.

Louisa May Alcott, who served as a nurse under her, said Dorothea was respected, but “not well-liked by her nurses, who tended to ‘steer clear’ of her.”

Many doctors did not want female nurses in their hospitals. Dorothea fought against them because she had the power to hire and fire nurses, not the doctors.

No matter how much they needed her skills, the War Department introduced Order No. 351 in October 1863, which effectively ended her authority. It gave the Surgeon General (Joseph K. Barnes) and the Superintendent of Army Nurses (Dorothea Dix), the power to appoint female nurses. It also gave doctors the power of assigning employees and nurses at hospitals. Dorothea resigned in August 1865.

Still seeking ways to help others, Dorothea returned to the role of social reformer. She traveled in Europe and wrote whenever she could to offer guidance in the widespread movement she created to reform the treatment of people living with mental health issues.

In 1843, there were 13 mental hospitals in the country; by 1880 there were 123, and Dorothea Dix played a direct role in founding 32 of them.

Hospitals were redesigned and new ones founded to fit the principles she spoke about. One such hospital would play a large role in my life.

The Middletown State Homeopathic Hospital was designed for the treatment of mental disorders. It opened on April 20, 1874. It was the first purely homeopathic hospital for mental disorders in the United States. It employed a number of Dorothea’s ideals as well as many new techniques for the treatment of mental disorders.

The most notable and often written about technique was the use of baseball as therapy.

The medical superintendent of the Middletown, New York, State Hospital for the Insane emphasized in his 1890 annual report the remedial qualities of baseball, boasting that for two seasons his institution had operated an organized and fully equipped baseball club of “acknowledged skill and reputation,” trained by an amateur player.

Ninety years later, I played on those same fields surrounded by trees along its edges. I could stand on the pitchers mound and everything else in my world – the stress, the anxiety, the trauma – went away. It was me and the batter. Nothing else mattered. It was, indeed, therapeutic.

Dorothea Dix died on July 17, 1887, age eighty-five, in a New Jersey hospital she had built several years before. She had been so revered, the state legislature had designated a private suite there for her to use until her passing.

I used to ride my bike along Dorothea Dix Drive, looking at the big, impressive houses belonging to the doctors who lived on the campus of the Middletown Psychiatric Center. Later, my grandmother would drive me along the same road to take me to my baseball game or to pick my mom up from work. I would look up at the names of the roads and wonder who they were named after.

There’s a reason and a story behind street names many never think about. I’m glad asked my mom who Dorothea Dix was. She may have been a hard ass at times, but I think what she accomplished was worth it.