The lesson here is to never make women angry. They may start a revolution.

The late 1700s saw much upheaval in the way of life among the French. One of the main concerns had centered around food.

In 1774, Turgot, Louis XVI’s controller-general of finances deregulated the grain market after several poor harvests. This led to the Flour War in 1775.

Famine was an ever present concern for those in the lower strata of society. Rumors abounded over a supposed conspiracy, the Pacte de Famine, which said the rich were planning to starve the poor to death.

Rumors of a food shortage led to the Réveillon riots in April 1789. Another rumor said the aristocrats were planning to destroy wheat crops to starve the people, provoking the Great Fear during the summer of 1789.

It was common to spend half your wages on bread.

Inflation and food shortages were commonplace in Paris. So was violence in the marketplaces. Mass demonstrations at Versailles were made. The Marquis of Saint-Huruge, a popular orator at the royal palace, attempted to evict deputies who were protecting the king’s veto power. He failed, but revolutionaries took hold of the idea and demanded the king accept the Assembly’s laws.

Throughout the summer of 1789, this idea simmered among the revolutionaries. The air grew tense as the months dragged on. Many nobles and foreigners fled Paris and Versailles in an attempt to avoid being involved in any conflict.

These events set into motion the Women’s March on Versailles, or the October Days. It would become known as one of the earliest, and most significant, events of the French Revolution.

On the morning of Oct. 5, 1789, women in the marketplaces in Paris were angry and ready to riot over the scarcity, and thus high price of bread.

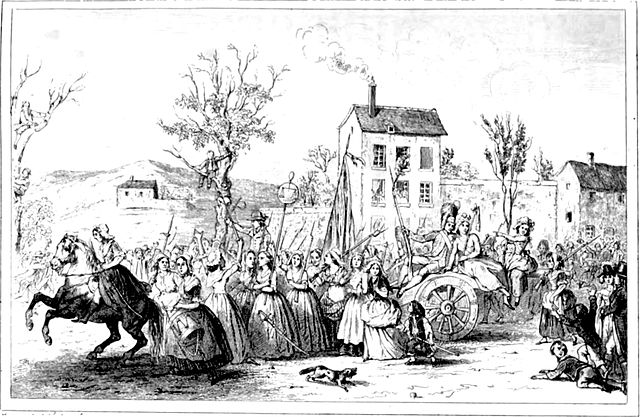

A young woman beat a marching drum and the women started marching. They began at the Faubourg Saint-Antoine in eastern Paris. Along the way, they forced a church to toll its bells. As they marched, more joined in.

As the numbers grew, women who joined carried kitchen bladed and other makeshift weapons. The tocsins rang loudly in each district they passed. Reports of six to seven thousand, possibly as high as ten thousand, women, and men, gathered at the Hôtel de Ville (Paris City Hall), known then as Place de Grève, and demanded bread and arms.

Stanislas-Marie Maillard, the first revolutionary to get inside the Bastille, was there, too. He was popular among the market-women helped to quell some of the more disturbing forces in the mob. He did nothing while City Hall was ransacked. The crowd stole provisions and weapons, including cannons. Maillard did, however, prevent the building from being burned to the ground.

The rain began pouring down and the crowd returned to the streets ready to move on to Versailles. The women’s march was now intertwined with the revolutionaries seeking political reforms and a constitutional monarchy. Maillard deputized many women, making them group leaders as he led the mob toward the palace.

The Marquis de Lafayette was to lead thousands of national guardsmen to protect the king. As they were assembling, Lafayette soon learned many of his men agreed with the rioters and were threatening to defect. The government in Paris asked Lafayette to guide the mob and request the king return voluntarily to Paris.

At 4:15 p.m., fifteen thousand guards and several thousand more civilians headed toward Versailles. It took six hours for the crowd to reach the palace. Along the way, they gathered more supporters. Talk among the crowd was about bringing the king back home to Paris and calls for the death of Marie Antoinette.

At Versailles, they joined with another group. Members of the Assembly greeted the crowd and invited Maillard in. While he was speaking about the people’s need for food – particularly bread – the crowd walked into the Assembly and sat on the deputies’ benches. They were soaked from the rain, tired from the thirteen mile walk, and hungry.

Reformist Deputy Mirabeau spoke with several of the women. Maximilien Robespierre, who was relatively unknown at this point in time, welcomed the marchers. He expressed strong support for the women. His words seemed to calm the crowd.

Six of the market-women were nominated to join Jean Joseph Mounier, the president of the assembly, to see the king. It was reported the king responded sympathetically. Food was disbursed from the royal stores and more was promised. The crowd thought they had achieved their goals. The six women and Maillard felt triumphant and returned to Paris.

Most of the crowd, however, felt the women had been conned by the king. They believed the queen would force the king to break his promises to the women.

After speaking with his advisors, the king said he would accept the August decrees and the Declaration of the Rights of Man without qualifications. He thought hostilities were over.

Lafayette went to see the king. The crowd called him a traitor, particularly for how he controlled the march, slowing its pace on its way to Versailles. Overnight, the women and the national guards had made an alliance.

Around 6 a.m., protesters entered the palace through an unguarded gate. They were looking for Marie Antoinette’s bedchamber. Royal guards attempted to lock them in that area of the palace. They fired at the intruders and killed a young protester. The crowd went nuts and surged further into the palace.

Miomandre and Tardivet, two of the royal guards separately attempted to quell the crowd. Tardivet’s head was cut off and raised on a pike.

While everyone was screaming and shouting, the queen and her ladies ran to the king’s bedchamber. They furiously banged on the door until the king unlocked the door and let them in.

Other guards were beaten. At least one more was killed, his head set on a pike.

With their savagery assuaged for the moment, everyone began to talk. Lafayette spoke to the national guard, now a militia, and the royal gardes du corps. The crowd was still outside and the Flanders Regiment and Montmorency Dragoons were unwilling to fight against the people. Lafayette convinced the king to speak to the crowd. He said he would return to Paris, news that pleased the crowd.

The crowd, however, also wanted the queen. She came to the balcony with her son and daughter. The crowd demanded the children leave. Fortunately, Marie Antoinette was a slick talker and she avoided being killed.

On Oct. 6, 1789, the crowd escorted the royal family and one hundred deputies to Paris. The national guard led the way. Guardsman placed loaves of bread on the tips of their bayonets and raised them in the air. The market-women road along with a captured cannon. It wasn’t all fun. Some carried the pikes with the heads of dead guardsman. Others sent gunshots over the royal carriage celebrating their victory. The king understood. He was now at the mercy of the people.

The king returned to the Tuileries Palace. The “Mothers of the Nation” were praised and were sought after for many years by the government. The king was forced to relent, signing the first French constitution on Sept. 3, 1791.

The storming of the Bastille and the Women’s march played major roles in sparking the revolution. The monarchy in France never recovered.

Marie Antoinette is to have famously said, “Qu’ils mangent de la brioche,” upon hearing the peasants were starving. While we know it as “Let them eat cake,” a mistranslation, the peasants couldn’t afford the expensive brioche either.

I wonder what would have happened if the market-women had just been given some ordinary, affordable bread.