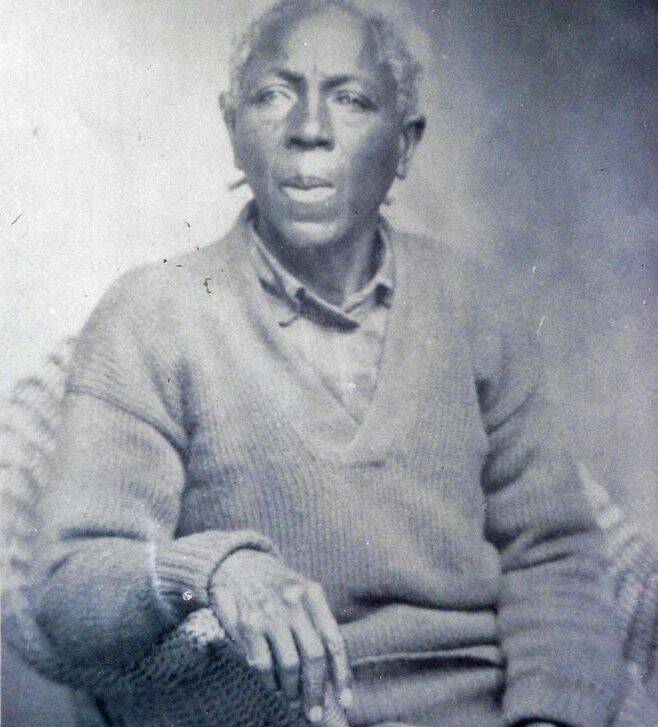

She was taken from Africa when she was two years old. She was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Despite continued racism in the United States, she remained rebellious and was, in many respects, a woman ahead of her time.

In July 1860, two-year old Matilda McCrear was taken with her three older sisters and mother, Grace, from their home in Dahomey, West Africa (Benin) and put on the Clotilda, the last known slave transport ship from West Africa to the United States. Her two brothers and father were left in West Africa. Matilda was the last living survivor of the transatlantic slave trade.

Matilda, Gracie, and her ten-year old sister, Sallie, were bought by Memorable Walker Creagh, a plantation owner in Mobile Alabama. She never saw her other siblings again. Gracie was forcibly paired with Guy, who was also on the Clotilda.

Matilda was considered lucky by most. She was able to stay with her mother. She was taken at a young age and she was emancipated while she was still young. That didn’t mean her life was easy. Matilda still witnessed the horrors of slavery and life was difficult for all freed slaves even after emancipation.

Soon after arriving at the plantation, Matilda, Grace, and Sallie tried to escape, but were recaptured.

After emancipation, she and her family continued to work the land as sharecroppers. It was often the only work available to blacks and it kept them trapped in poverty. Sharecroppers were often abused and Matilda still had to deal with segregation and being a black farmer during the Depression. According to research, Grace never learned much English.

She never told her story to her descendants, but her resilience during a dark period of American history provides a ray of hope for those who must endure slavery.

Matilda never did what society expected of a black woman in the South. She never married. She participated in a decades-long common law marriage with a white German-born, Jewish man. The couple had fourteen children.

Her grandson, Johnny Crear, told CNN it was difficult to learn about his grandmother’s story.

“Her story gives me mixed emotions because if she hadn’t been brought here, I wouldn’t be here. But it’s hard to read about what she experienced,” said Crear.

However the stories of her resistance to oppression fitted with what he had been told about his grandmother. “I was told she was quite rambunctious,” he said.

After abolition, she worked as a sharecropper, as did many former slaves.

Matilda never married, but, according to her grandson, had fourteen children with a white, German-born man. She changed her last name from Creagh, her slavemaster’s spelling, to McCrear.

When she was in her seventies, she filed a legal claim against the government for compensation for her enslavement. Cudjo ‘Kossola’ Lewis, who was thought at the time to be the last survivor of the Clotilda, had filed a claim and received some financial assistance. Matilda and Redoshi, the formerly oldest known survivor of the Clotilda, wanted to meet him. The elderly women made the three hundred mile round trip journey from rural Dallas County to Africatown, near Mobile, in December 1931.

After returning home, Matilda walked, “15 miles on dirt roads to a county courthouse to make a claim for compensation for her enslavement.” She filed a claim for herself and Redoshi. Matilda’s claim was dismissed.

To even make an attempt at reparation for slavery was an act many poor, black women would never think of doing. Matilda attracted the attention of the local press. Those interviews have filled in details about her life that would have otherwise been lost.

We know about Matilda thanks to another remarkable woman, Hannah Durkin, of Newcastle University, who researched the story. If you have access, you can read the paper online. If you do not have access and want to read the 28-page paper, I have a copy. Hannah discovered the story while conducting research and came across a story in the Selma Times-Journal. Journalist Octavia Wynn interviewed Matilda after her case for compensation was rejected.

Throughout her life, Matilda never forgot her roots. She wore her hair in the traditional Yoruba style and had the traditional rite facial scars.

She also found some of her people. A settlement of the descendants of slaves from the Clotilda was near Mobile, Alabama. They gathered often and spoke Yoruba with each other.

Matilda died at age 83 in January 1940, in Selma, Alabama. Her story is one of a few known of female slave trade survivors. It is, “the first to describe a West African family’s experiences of transatlantic slavery and its aftermath.” There was no obituary or recognition of her life.

“There was a lot of stigma attached to having been a slave,” Dr Durkin says.

“The shame was placed on the people who were enslaved, rather than the slavers.”

Her grandson was not surprised at the cruelty Matilda endured.

“From the day the first African was brought to this continent as a slave, we’ve had to fight for freedom,” he says.

He grew up in an era of racial segregation – and his parents put a huge emphasis on education as the way to escape poverty and the “key to changing the world”.

In the civil rights protests, they were singing songs with roots in the years of slavery, he says, tapping into the same “continuous struggle and fight” and pursuing the same the goals of “real freedom and equality” as his independent-minded grandmother.

“It’s refreshing to know she had the kind of spirit that’s uplifting,” he says.

Her spirit continues to live on today in everyone who fights for equality and justice all around the world.