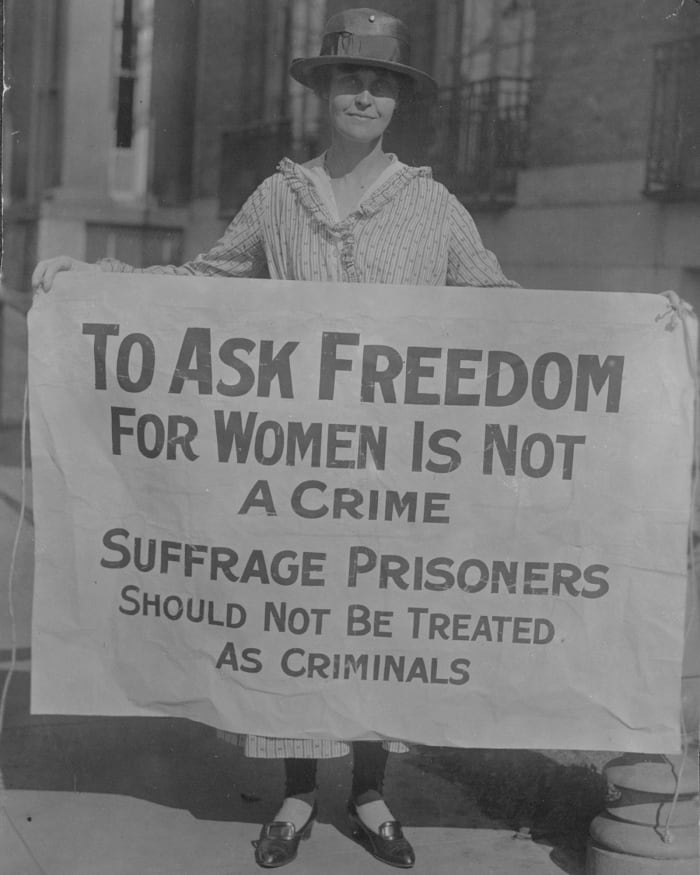

When schools teach about women’s suffrage and the struggle to allow women the right to vote in America, we get the neat package. We hear tales of letter-writing campaigns, of activists walking in the streets holding signs, and of women giving rousing speeches. We are told President Woodrow Wilson supported them, which he eventually did. We learn that some were arrested. What we never hear is the story of how they were treated.

The suffragists who were beaten and tortured during the “Night of Terror” is rarely told.

Their story begins on Jan. 9, 1917, when the Silent Sentinels, suffragists from the National Women’s Party, began protesting in front of the White House after meeting with President Woodrow Wilson. They picketed and silently protested at the White House until their demands were met two and a half years later.

Many women were arrested, but quickly released. As time went on, that began to change. The women began receiving long jail sentences for protesting.

On June 22, Lucy Burns and Katherine Morey were arrested for obstructing traffic. They had carried a banner citing the president’s speech to Congress. It read, “We shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments.”

Twelve more women were arrested on June 25 on the same charge. Their sentence was three days in jail or a $10 fine. They chose jail. On July 14, sixteen women were arrested and sentenced to sixty days in jail or a $25 fine. They chose jail. (Note: $10 in 1917 is $221.53 in 2020 and $25 is $553.82.)

The number of women arrested was more than the District of Columbia Jail could handle. Many were transferred to the Occoquan Workhouse, a prison in Northern Virginia.

The women were required to hand over their belongings. They were taken to the showers where they were ordered to strip and bathe. According to “Jailed for Freedom,” by suffragette Doris Stevens, there was only one bar of soap for the entire workhouse, so all the suffragists refused to use it.

They were given prison clothing and given dinner. Most could not eat the food because it was rancid. Later, the women would hold competitions to see who could find the most worms in their food.

A governmental committee was formed in September 1917 to “deal with” women’s suffrage. Massachucetts Rep. Joseph Walsh opposed the committee claiming the government was “yielding to the nagging of iron-jawed angels,” who were “bewildered, deluded creatures with short skirts and short hair.”

The more the women protested, the longer their jail terms became. Co-founder Alice Paul was arrested on Oct. 20. She was carrying another banner with a quote from Wilson that said, “The time has come to conquer or submit, for us there can be but one choice. We have made it.”

She was sentenced to seven months in district jail. She was given two weeks solitary confinement. Her only sustenance was bread and water. She was taken to the prison hospital because she became so weak. There, other women joined her in her hunger strike.

Doctors force-fed the women with raw eggs mixed with milk. After not eating for so long, their stomachs couldn’t handle the large protein influx and vomited.

The treatment of the suffragists was about to get worse.

On Nov. 14, 1917, thirty-three suffragists were sent to the Occoquan Workhouse, a prison in Northern Virginia, and faced a variety of forms of torture. By the end of the night, they were barely alive.

The male guards at the Northern Virginia prison manacled the party’s co-founder Lucy Burns by her hands to the bars above her cell and forced her to stand all night. Dorothy Day, who would later establish the Catholic Worker houses, had her arm twisted behind her back and was slammed twice over the back of an iron bench.

The guards threw suffragist Dora Lewis into a dark cell and smashed her head against an iron bed, knocking her out. Lewis’s cellmate, Alice Cosu, believing Lewis dead, suffered a heart attack and was denied medical care until the next morning.

The guards also beat, choked, dragged, and kicked other women.

Newspapers ran stories about how the suffragists were being treated, angering some and gaining more support for the constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote.

All the protesters were released on Nov. 27 and 28. Alice Paul had spent five weeks in prison, refusing to give in.

In the beginning of 1918, the Washington, D.C., court of appeals found the women had been “illegally arrested, convicted, and imprisoned.”

President Woodrow Wilson announced his support for the 19th amendment on Jan. 9, 1918. The House of Representatives barely passed the amendment, but the Senate refused to take the matter up until the following October. When they did, it failed by two votes.

Arrests of the protesters at the White House resumed on Aug. 6, 1918. Protesters began burning Wilson’s words in “watch fires” in front of the White House on Dec. 16, 1918. They burned Wilson in effigy on Feb. 9, 1919.

Alice Paul spent that year encouraging citizens to vote anti-suffragists from Congress. Her tactics worked. The House of Representatives passed the amendment on May 21, 1919, followed by the Senate on June 4. Alice Paul’s work wasn’t finished. She still needed three-fourths of the states to ratify the amendment.

After Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to vote for ratification, the 19th Amendment was officially ratified on Aug. 26, 1920.

Doris Stevens published, “Jailed for Freedoom,” in 1920 recounting the things the suffragettes endured.

There are two ways in which this story might be told. It might be told as a tragic and harrowing tale of martyrdom. Or it might be told as a ruthless enterprise of compelling a hostile administration to subject women to martyrdom in order to hasten its surrender. The truth is, it has elements of both ruthlessness and martyrdom.

But it was never martyrdom for its own sake. It was martyrdom used for a practical purpose.

The Occoquan Workhouse became the Lorton Reformatory, a prison complex that remained open until November 2001. The Lorton Arts Council took over in 2002 and, after extensive renovations, opened the Workhouse Art Center. It includes the Lucy Burns Museum, which retells the ninety-one year history of the prison and the story of the suffragettes who were imprisoned there.

Jina Red Nest

Good