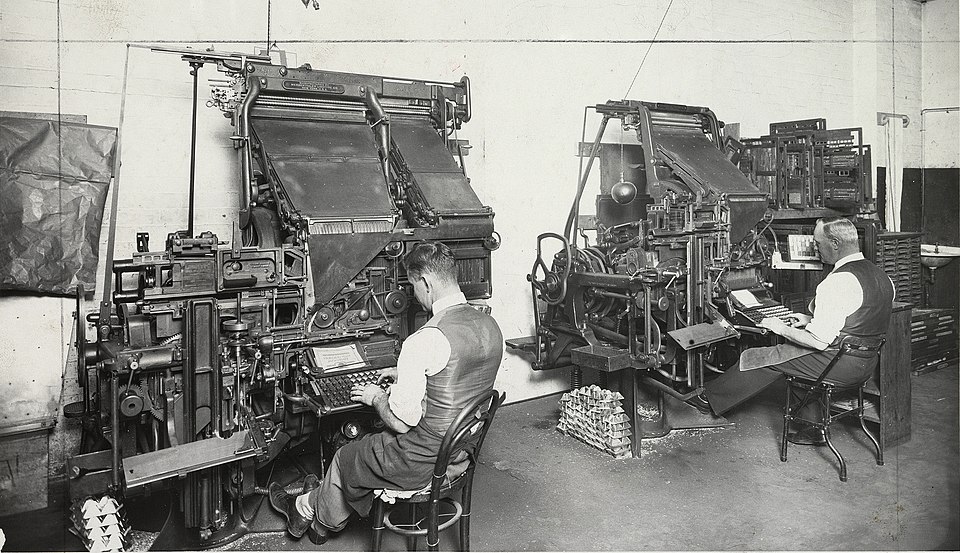

Linotype machines, Anthony Hordern and Sons department store, c. 1935, gelatin silver print, from Anthony Hordern and Sons pictorial collection.

My apologies for being late this month with this post. If you read my post “October wins, but by less of a margin,” you understand why. Now onto three documentaries which helped keep me going.

Independent Lens: I am not your Negro

“I am not your Negro” is a film that takes you through James Baldwin’s unfinished project about the lives and assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., while examining race in America. It was nominated for a Peabody Award. Though the film is now 5.5 years old, it’s still relevant today as not much has changed in America since it came out.

Baldwin intended on calling his next project, “Remember This House.” He had already begun working on it in 1979, but, when he died in 1987, he had only completed 30 pages.

Raoul Peck does a phenomenal job with this piece of work and I think Samuel L. Jackson was a great choice for speaking Baldwin’s original words. The film uses a lot of incredible archival footage throughout, including a part of an interview with Baldwin.

“I can’t be a pessimist, because I’m alive to be a pessimist means you’ve agreed that human life is an academic matter. So, I’m forced to be an optimist. I’m forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive. But [pause] The Negro in this country, the future of the Negro in this country is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country. It is entirely up to the American people and our representatives, It is entirely up to the American people whether or not they are going to face and deal with and embrace this stranger whom they maligned so long.

“What white people have to do is try to find out in their own hearts, why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place, because I’m not a nigger. I’m a man. But if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need him. And the question you got to ask yourself, the white population of this country has got to ask itself. North and South, because it’s one country, and for the Negro there is no difference between the North and the South. There’s just a difference in the way they castrate you, but the facts of the castration is the American fact. If I’m not the nigger here and you invented him, you the white people invented him, they you got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that, whether or not it’s able to ask that question.”

Through Baldwin’s powerful words and writings, the viewer is forced to look deeper at what America is and who she stands for. For anyone living under the delusion that we solved all our race issues when Barack Obama became president, “I am not your Negro” challenges every presumption you have and reminds viewers that we still have so much farther to go.

Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it has been faced. History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals.

You can watch “I am not your Negro” on Amazon and AppleTV.

Reel Injun is a 2009 documentary directed by Cree filmmakers Neil Diamond, Catherine Bainbridge, and Jeremiah Hayes, and explores the portrayal of Native Americans in film.

After watching the film, I contacted my friend, Jina. Until I watched this film, I didn’t know her aunt, Dawn Little Sky, was also an actress. I only knew her as the lady who painted the Winter Count, which is on display at Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. Dawn passed away a couple of weeks ago at the age of 95.

To me, this is why these documentaries are so important. They not only teach us, they cause us to ask questions and talk with friends where you learn new things.

“Reel Injun” takes us through the portrayals of Native Americans in Hollywood movies, complete with the racist stereotypes of the “noble savage” and “drunken Indian.” You learn about a guy named Iron Eyes Cody, who was an Italian-American, but made people believe he was Native American. Jews and Italian-Americans were often used as stand-ins for Native Americans on film instead of, you know, going and hiring actual Native Americans.

I absolutely loved what they thought about films like Dances With Wolves, a “film about a white guy.” I think that’s why I never truly understood why the people I knew at the time the movie came out liked the movie. I was too damn focused on the Native Americans and what they were doing. I guess I watched the movie wrong. Or maybe I’m the weirdo and missed the point of the movie.

Diamond was partially inspired to make the film after thinking about his childhood experiences playing cowboys and Indians. Everyone was a Native American, but they all wanted to be the cowboy. Throughout his life, he has questioned the portrayal of his people and learned most people got their ideas of what a Native American was by what was in the movies.

The film is funny, eye-opening, and sometimes shocking. It blends in many the many different aspects of Native life on film in such a way that it never felt too overwhelming and I wanted to see more.

It is available for viewing on Amazon. You can watch it on YouTube in Spanish. I would advise against watching it on PBS as the film was cut by more than half and things don’t make as much sense. I watched the PBS version after I watched the film and kept going, “wait” and “why the fuck did you cut that?” Then again, it kind of proved the filmmakers’ point.

Linotype the film: The Eighth Wonder of the World

Thomas Edison called the Linotype the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” He was right. Linotype completely revolutionized mass printing and with it society as a whole. Its effects were felt for more than 100 years before digital took over and, even then, the Internet owes itself a debt of gratitude to the linotype machine. The film details not only how the machine impacted the world, but tells an emotional story of the people who ran the machines.

Linotype and letterpress printing allowed for the production of daily newspapers. It standardized an industry which included newspapers, magazines and posters. Ottmar Mergenthaler’s creation in 1884 kicked off change on a worldwide scale.

While watching the film, I was reminded of a coworker, Jack Hartshorn, who used to tell me stories of how it worked. He showed me the scars on his leg from working with the molten lead. We should have recorded those stories before he died. Jack was a great source of information on the newspaper industry and his stories made it easier for me to follow along with the film because I knew how the machines worked before ever watching this documentary.

By 1904, there were 10,000 Linotypes in use. It grew to 100,000 by 1954 and was the standard use machine by the end of the 1960s. Although they were made obsolete in the 1970s with new technology, Linotypes changed the world.

The film is an emotional one which includes the people trying to keep the machine alive. If you really listen to the film, you will hear a message of slow down. Take your time to listen to the machines, to the world, to everything and try to imagine what life would have been like without Linotype.

Imagine the knowledge the world would not have access to if this important precursor to mass knowledge had never been made. We take so many of our modern conveniences, including cell phones, for granted. We don’t realize that the whirring, clicking, and sometimes obnoxiously loud clanking of a century old machine helped to build what we have now.

If you don’t know how Linotypes worked, have no fear. You learn how in the film. If you want to learn how literacy rates exploded after the invention of the Linotype, it’s here. If you want to see a tribute to a mechanical behemoth that changed the world, watch the film.

Quite simply, Linotype helped to preserve knowledge and culture while also teaching the world to read in a cheaper, more accessible way.

You can watch the documentary on the filmaker’s website, YouTube, Amazon and Tubi.

Normally, I don’t recommend reading the comments on YouTube, but there are some neat little stories from people who used Linotype machines or had family members who did.