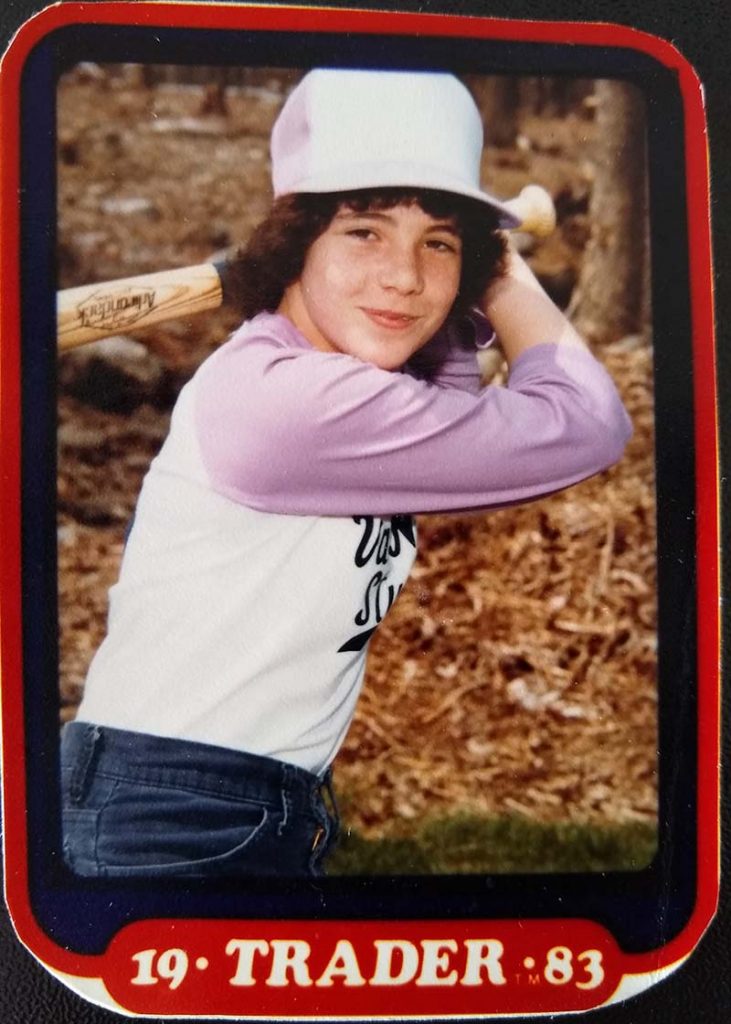

Bats: L; Hits L; BA: .367; ERA: 1.97; Age: 13; Height 5ft. 0in.; Weight: 95 pounds; Position; P, 1st

I stared at the signs Stacy was showing 60 feet away. I shook her off a few times before settling in on my “go-to” pitch. I could place it almost anywhere.

Standing on the pitcher’s mound, the entire world melted away. My teammates knew I liked it quiet, so the normal cheers of encouragement were rarely heard when I was on the mound. I shut out the people screaming in the stands. It was just me, the catcher, and the batter.

I turned the ball over in my glove several times until I got the grip I liked. I could never get used to the way I should be holding the ball. I had to always have my forefinger on a seam and so I adjusted my throws accordingly. I tightened and then loosened my grip on the ball before sending it screaming toward home plate.

Strike three. Two outs.

As my teammates tossed the ball around the infield after the strikeout, I wandered around the pitcher’s mound. I chewed on a piece of Fruit Stripes gum. They say every ball player has a superstition they believe makes them successful. Chewing gum was mine. I was so convinced of it, my coach always carried a pack of gum with her in case I forgot mine.

Being left-handed in the 1970s meant I was destined to pitch and play first base. I actually tried out shortstop, but hated the position. I was good at the other two positions. A lefty has the advantage of a longer reach at first base, which translates into fractions of a second which can make the difference between a runner being safe and being out.

I was a decent hitter, often being placed at #2 or #3 in the lineup. My coach had also helped me perfect the drag bunt. I rarely got out. The purpose of bunting is to sacrifice yourself so your teammate, or runner, has an almost guaranteed chance of advancing to the next base.

A lefty batter with a good drag bunt confounds the other team. There is a natural instinct to not run into another person as well as a natural fear not to hit the runner with the ball. I was good at getting the ball to go at least halfway down to first base before the girls on the other team would pick it up. Often, the catcher hesitated because I was blocking a throw to first base, forcing the pitcher to pick up the ball and throw it at an awkward angle so she didn’t hit me in the head. Drag bunts gave me a decent chance of making it to first base safely.

Pitching, however, seemed to come naturally to me. I could remember most of the batters in our league, what their weaknesses were, and which pitches they were likely to swing at.

Another batter came up to the plate. I had been playing against this girl for almost four years. She was tough. I didn’t always win. She rarely struck out. She usually got a piece of the ball and hung in there, fouling off pitch after pitch, until she could put the ball in play.

If I was on my game, I got her to hit a grounder to the infield. If I was off my game, she had the power to knock it out of the park. I was only about 90 percent on my game this day. I didn’t want to throw a fastball at all to her. No one would ever see that ball again if she got a hold of it.

Every time Stacy signed a fastball, I shook her off. I wasn’t going there today. She gave me the sign over and over until I relented. My pitch skirted the edge of the plate. The batter didn’t go for it. The umpire yelled, “Ball.” Not the best way to start, especially since I thought it got enough of the plate to be a strike.

“What’s wrong with you?” my grandmother yelled from the stands. She wasn’t talking to me. “Do you need glasses?”

The umpire turned and looked at her. She stared him down. He turned back around and prepared for my next pitch.

I chewed my gum and blew a bubble. I waived off another fastball. I waived it off several times. We agreed on a slider.

I turned the ball in my hand, hiding which pitch I was setting up for from the runner on second base. It’s not like she would know which pitch I was going to throw. I didn’t hold the ball correctly anyway.

At the time, my pitching sometimes resembled Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher Kent Tekulve. As my arm came forward and I was about to release the ball, my hand turned over on the ball and I let loose.

This entire motion caused the ball to be momentarily hidden behind my body and then released with unusual spin. None of my coaches ever tried to correct it because it worked, but I always wondered if it was normal.

The ball sailed from left to right, ending in the catcher’s mitt on the inside of the batter.

“Ball 2,” the ump said.

“What?” I said. I took a few steps forward, my hands in the air. I squinted at him. Stacy stood up and threw the ball back to me. She motioned with her hand for me to stop walking toward home plate. She started yelling at the umpire.

Stacy wasn’t the only one upset. It seemed the crowd in the stands thought the umpire was wrong, too. My grandmother was livid. The umpire was staring at her. She took off her glasses and held them out toward him.

“Here,” she said. “You obviously need them more than I do.”

The umpire told her to sit down. They argued back and forth a few times.

“You’re a damned blind fool if you couldn’t see that was a strike,” she said.

The umpire threw her out of the stands. She kept yelling back at him as she walked away. She watched and scored the rest of the game while leaning on the fence separating the parking lot from the ball field.

I didn’t understand the science behind anything I threw. I was 13-years old. I knew what felt right and how to push the ball out of my hand to make it go where I wanted to go. Everyone called my slider a slider because of the way it appeared to move to them. It wasn’t quite a real slider and sometimes I could make it sink like a sinkerball. A cutter today really resembles what I used to throw, but even then, not 100 percent.

Gram helped me with my release point, but because I had a weird release and a weird way of holding the ball, it was just the pitch Gram taught me to throw. My catcher just wanted to know when I was going to throw it so she could prepare for where it was going. I didn’t really care about a name. I just knew it worked.

Since I knew this batter well, I knew she wasn’t going to swing on a 2-0 count. I threw a fastball as hard as I could right over the meat of the plate. Strike 1.

A 2-1 count is a hitter’s count. As the pitcher, I had to throw something she had to swing at, but hopefully not put into play. She fouled off half a dozen pitches. The count remained at 2-2 for what seemed like forever.

After waiving off several fastballs, Stacy made a visit to the mound. The rest of the infield joined her. My coach stood by the dugout, leaning against the fence meant to keep foul balls from flying into the dugout. I told Stacy my arm was getting tired. My teammates provided some encouragement. Let her hit the ball, but try to get it low so she’d hit a grounder was the consensus. They’d pick me up so I didn’t have to do it all alone. We agreed on my go-to pitch, but on the inside.

Stacy set up behind the plate. She gave me a target on the outside of the plate. We knew this wasn’t where I was going to throw it, but waited just long enough for the runner on second to relay the target. The batter glanced down at the plate. I smiled.

The ball cut through the air, moving from my left to right. The batter connected. The ball tore across the grass and onto the dirt along the third base side. I saw Sherry grab the ball in her glove. As she pulled it out of her glove and into her right hand, I instinctively dropped to the ground. She could throw a ball close to 90 miles per hour from third to first and my head wanted no part of that.

Kneeling on the ground, I turned to watch the ball land in the first baseman’s mitt. Out. Side over. I pumped my fist and walked toward our team’s dugout on the first base side of the field. Sherry patted me on the back. “Nice one,” she said.

In the near distance, I heard, “Good job, Irene.” I looked at my grandmother. She smiled and waved. I waved back. The umpire stared at her, but he could do nothing. Technically, she was in the parking lot.

Katie

I can tell you spent a ton of time working on this. It really has a lot of depth and polish. Also, I LOVE your baseball card photo. That look of joyous confidence on your face!