I was finishing up for the day at the Star-Herald when I received a text message I was hoping not to get. It was from her.

“Are you sure you don’t want to do it?”

In the thirty or forty seconds it took for me to respond to the text, my brain went through all the scenarios of doing or not doing an interview for the local television station about the importance of Colin Kaepernick taking a knee.

I thought about how I was taught everyone was equal. I thought about the separate water fountains and bathrooms my hometown used to have. I thought about the little divider at the lunch counter in every Woolworth’s I’d ever been in.

I thought about the time my nephew beat up a Muslim classmate a few weeks after 9/11 because he thought it was cool. I thought about my racist family members. I thought about the words I heard growing up – jigaboo, porch monkey, spic, chink, gook – and the power those words had to hurt others.

I thought about the year I lived in Southern Pines, North Carolina where so many people treated African-Americans as second-class citizens. I thought about the time I stood in line at the Food Lion and a white woman in a fur coat refused to touch the cashier. She put her money on the conveyor belt and the cashier had to give the change the same way. I bit my tongue hard. I wanted to ask the lady what she was afraid of. I said nothing. I regret to this day I didn’t speak up.

As I paid for my groceries, I made small talk with the cashier and handed her my money. She put my change in my hand. As I was putting the money in my pocket, the cashier said, “You’re not from around here, are you?” No, I wasn’t. We both knew what had just occurred. The cashier seemed resigned to it.

All over town, I saw white people in positions of authority while African-Americans were doing the menial jobs. I never saw a white gardener the year I lived there.

I thought about my husband’s coworker who was still angry his family lost their plantation more than 100 years ago during the American Civil War.

I thought about the time I got into a fight in high school defending an African-American classmate. The fight isn’t something I’m proud of even though I was defending a classmate from a bully in Physical Education (PE) class.

I never understood why this one girl hated my classmate so much. I tried to be the mediator. When it didn’t work, I went to the PE teachers – we had four – and nothing was done. I went to the four guidance counselors. Nothing changed. I went to the two assistant principals. Nothing.

I tried one last time to get this girl to stop calling my classmate derogatory names and threatening her. I still remember the words she said to me.

“Why the fuck do you care anyway? She’s nothing and you’re a pathetic nigger lover.”

I went from zero to rage in an instant. By the time my brain began to catch up to my body, my fist was already crushing the girl’s face. She would have fallen over, but hit the gym lockers instead. She hit back. We exchanged blows.

At some point, I got the upper hand and knocked her down. I climbed on top of her and kept swinging. I don’t remember most of what happened. I only know what people told me later.

I tore the girl’s shirt. I held her down with my right hand and continued striking her with my left fist.

One of the PE teachers tried to stop the fight. She grabbed my left arm. I pulled free and punched her. Depending on the classmate telling the story, I either bloodied the PE teacher’s nose or broke it. A male PE teacher came into the locker room, lifted me off the girl, and carried me out to the hallway.

“Wait here,” he said.

“Fuck you,” I said. “I’ve got computer class.”

As I sat in computer class trying to get my BASIC program to work, Mr. G., my assistant principal, came into the room.

“Irene, I need to talk to you,” Mr. G. said. I got up and started to walk out of the classroom. “Bring your stuff. You’re not coming back.”

An audible “oooo,” was heard from my classmates. Most of them were in PE with me.

Mr. G., asked if I was hurt and if we needed to go to the nurse’s office before going to his office. My knuckles hurt, but I was otherwise fine. He called my mom.

“I don’t want you to smile or laugh,” my mom said. “You’re not in trouble, but you’re going to have to walk home.”

I gave the phone back to Mr. G. He spoke with my mom then hung up the phone. I was being suspended for three days.

Mr. G., also made me walk with him to all of my teachers, interrupt their classes, and explain why I was being kicked out of school. My first three teachers told me not to worry about making up the work.

We went to Mrs. House’s class next. She was my mentor. She knew what was going on and had suggested I follow the chain of command to get the bullying and racial slurs to stop. I looked at the floor when I told her what I had done.

I wasn’t particularly proud of resorting to violence to solve the problem. Today, as I think about events over the past thirty years, I did the same thing the oppressed have always done. They see an injustice and try to correct it. They are vocal and hold protests. The protests end up violent because law enforcement provoke the situation. Things get burned.

Violence should be a last resort, but I understand why things take that particular turn. I tried to do it the right way, but the system wouldn’t allow it.

When I finished telling Mrs. House what I had done, I expected to be admonished for my actions.

“It’s about time you took matters into your own hands, Irene,” she said. “You know damned well no one here is ever going to do anything about it.”

No one seemed to actually be mad about what I had done. I wasn’t supposed to fight, but I was being given a minimal punishment for the damage I had done. Sixteen-year old me was confused. My mom didn’t give me extra chores or additional punishment at home. I didn’t understand what white privilege was then. I do now.

My classmate and the girl I beat up eventually talked to each other. They became friends.

I picked up my cell phone and looked at the text again. “Are you sure you don’t want to do it?”

No. I’m not sure, but I think I have to.

Melanie Johnson, a reporter from the television station had read one of my columns where I defended Colin Kaepernick. She had been assigned to find someone who was willing to go on the record and say what I had written. She found them, but none would speak on the record.

I breathed in deeply through my nose and exhaled slowly through my mouth. I felt the right side of my bottom lip where I have partial nerve damage from that high school fight. I looked at my phone.

“Are you sure you don’t want to do it?”

I picked up my phone and texted back. “Yes. I will do it?”

We arranged to meet at the television station for the interview. I was nervous. I said a lot of things, but pissed off people by saying residents in western Nebraska didn’t understand the endemic racism that is embedded in society. They didn’t see it on a daily basis like I had.

When the interview was over, Melanie Johnson and one of her coworkers thanked me. Melanie said my voice carried more weight in this part of the country than if she had interviewed a minority. I sighed.

I hate she even had to say that sentence to me. My voice should not be more important because I am white. It angered me, but also reassured me I had made the right decision.

I had spoken to my editor about it earlier. He reminded me of the backlash I would receive. I didn’t care. I already received backlash each week with my column.

He recommended I not do it. I had told Melanie no and cowardly hid behind, “my boss recommended I don’t do it.”

My only regret is I didn’t let my editor know I had changed my mind. I honestly didn’t expect so many racists to be vocal. My editor received an email from three employees at the Star-Herald expressing their anger toward me.

Racists called and tried to justified themselves. I didn’t understand, “this is how it is here.” I got emails telling me I was, essentially, an interloper.

Again, white privilege prevented me from even being written up. I just got the, “I wish you hadn’t done that,” from my editor. That was it.

Nothing has changed. American cities are on fire and we have an administration in Washington condoning the police murdering a black man.

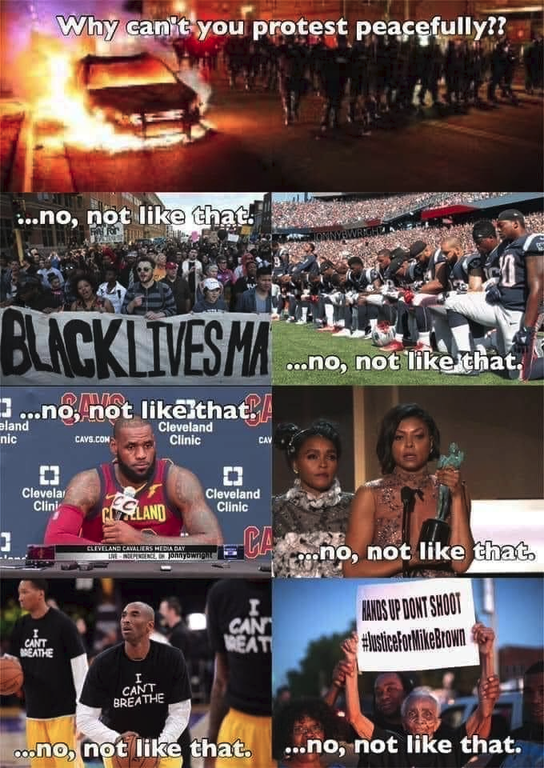

I want to hope this time things will change. I understand why Colin Kaepernick took a knee. Today, however, this is all I can think of:

Red

Compelling post.