“I gave you a B+ in my class instead of an A because I wanted you to participate more,” my poetry professor said. “You’re really good and have great insights, but you need to talk more.”

It made me angry. I was a junior in college and had heard similar comments from teachers and professors since the first day I stepped into kindergarten. I thought college professors were supposed to be enlightened and understanding of the different ways kids learn. I was wrong.

I didn’t always participate because the extroverted kid always raised their hand first, often chanting, “Oooo, pick me. Pick me.” I need time to contemplate my answer before I proceed with a thought out response. If you want my honest opinion on something, sometimes you need to wait. By telling a kid to participate more, you are providing them with more stress and anxiety they don’t need.

Then, there were the constant comparisons to my sister. The most common comment I heard K-12 was, “Are you Lorraine’s sister?” It was always asked in a snarky, condescending tone. My sister was loud, boisterous, and a general pain in the ass. She was always in trouble. Assumptions were made that I was the same and treated in the same manner as she.

The only teacher who ever apologized for that mistake was Ms. Prather, my 12th grade English teacher. About six weeks into the school year, she said, “I’m sorry I assumed you were going to be just like your sister. I was wrong and I will remember that in the future.”

Ms. Prather was a hard ass, always pushing kids to do more, to do better, but she admitted when she was wrong and I always respected her for that. She also taught me more about writing than any college professor ever did.

Her comments were made in October 1987. I still remember how much those words meant to me and that she treated me as Irene, not loud mouthed Lorraine’s little sister.

Mrs. Donnatin was my ninth grade science teacher. Although we had assigned seats – in alphabetical order – at the beginning of the year, she was mindful of all her students. I eventually had a seat on the right side of the room, with no desk partner so I could do my work. She never called on me unless I raised my hand.

I had Mrs. Donnatin again in eleventh grade for Earth Science. Since she knew me well, she put me in the back of the room with another student, a girl I played baseball with who was also introverted, and just let us do our thing. Whenever she came over during group work to ask if we were okay, she wasn’t checking on our science project.

Ms. Barnes, my eighth grade English teacher, is probably the teacher I hated most in school. I wrote – still do – smaller than most people. My record is thirty-three words on one line of loose leaf paper. Ms. Barnes refused to take anyone’s paper if they wrote smaller than her imaginary determination of how big a person should write. She seemed to take pleasure in embarrassing students as well. “Do you think if you write so tiny I won’t notice your mistakes?”

At first, I rewrote everything, trying to have meticulously clear penmanship. It took up an enormous amount of time, which resulted in more homework because I couldn’t keep up with the classwork and the constant rewrites. So, I stopped trying. I simply went back to my desk, either worked on what everyone else was doing or stared out the window.

Ms. Barnes’ classroom was on the third floor. The roof to the gym was outside her window. I would make up stories in my head about what the birds were doing on the roof. They hated Ms. Barnes, too.

After five or ten minutes had passed, I would take the same paper back up to her desk and turn it in. Sometimes, she would take it, sometimes she would tell me the words still weren’t big enough. I repeated the pattern until she took the paper. I never rewrote it. It was a battle of wills that I was determined to win.

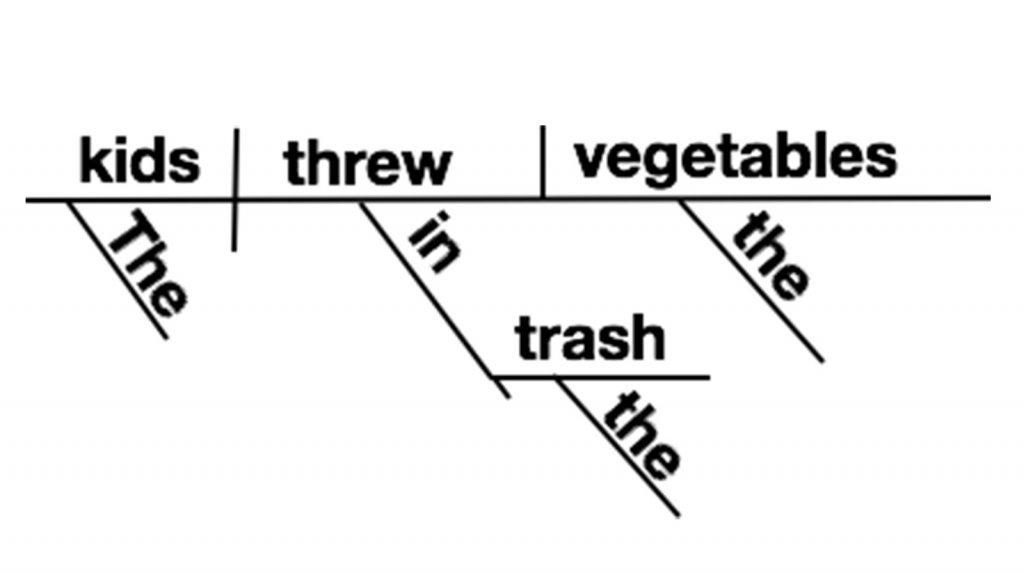

Ms. Barnes was a source of constant aggravation for me. Despite the fact that I was shy and introverted, she was one of many who contributed to my social anxiety. One thing I was really good at was diagramming sentences. Ms. Barnes often made students show their work on the chalkboard. She was not kind to the students who got something wrong. She would yell at me that I wrote too small and I needed to redo it. Occasionally, another student would take pity on me and yell from the back of the room they could see it just fine.

Junior high is a tough time for kids. They’re going through a lot of physical and emotional changes and there are days they don’t want to be in front of a classroom writing or reciting their Math, Science, and/or English assignments.

There’s a reason a girl who usually volunteers doesn’t one day or why a boy insists on taking a book up with them to the front of the room. The introverted kids are a little easier to spot and we’d prefer to volunteer instead of being ordered to the front of the room.

When I worked in Gering Public Schools as a special education paraeducator, Social Studies Teacher Michael Broderick and I had a system for one student I worked with. This student struggled a lot, but tried hard. When Michael would ask for the answer to a question, he would look at me. A simple thumbs up meant the student could answer the question. It made the kid feel less of a special education kid and more like the rest of his peers. The kids around him would say a “good job,” which often made his day.

When I was in fourth grade, students volunteered to put the chairs away after chorus practice. When I finally mustered up the courage to volunteer, the teacher told me I couldn’t do it because I was never in school. I reminded her that I had been ill and in the hospital for the past three weeks. Until then, I had never missed more than three or four school days per year. “I don’t believe you,” she said. “You’re not responsible enough to come to school, so I’m not going to let you do the chairs.”

I was angry. I still had three more years in elementary school where I was forced to be in her stupid class.

My kindergarten teacher was a rather rotund lady. She constantly compared me to my sister. She also made a point of saying things like, “You’re so smart, why don’t you talk more?” She was the first in a long line of teachers who put on my report card, “needs to participate more” and “needs to speak more in class.”

Being called upon to answer something on the spot was one of my worst nightmares in school. As someone who takes time to formulate an answer to everything, I dread hearing, “what do you think Irene?” I would prefer to say, “Can you give me a week to work that out?” Society, however, wants an answer now, so I ramble on with stupid words and phrases until the other person moves on.

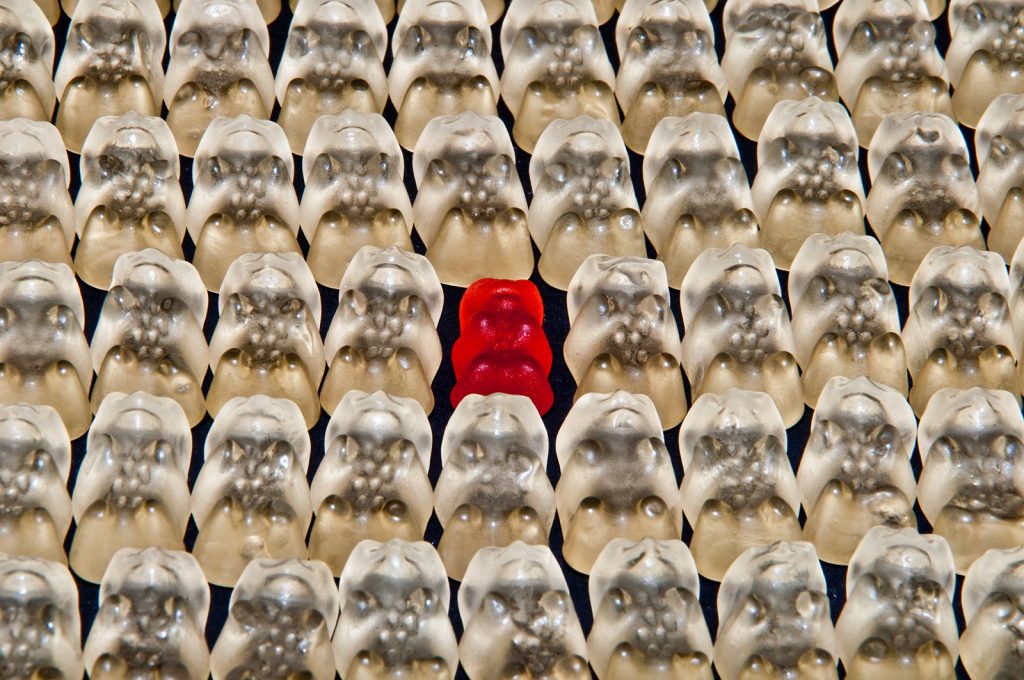

Shy, introverted, and/or socially anxious kids should never be forced to be like everyone else. Though I had a few teachers in school that valued and appreciated awkward, teenage me, I wish they had been the norm. From my experience, not much has changed in the thirty years since I left high school. Some schools (looking at you Scottsbluff Public Schools) have recognized this approach makes students more apprehensive. We all learn in different ways and throwing an introverted kid in the deep end is a recipe for disaster.

We all knew the “quiet kid” when we were in school. If you are like me, it was probably you. Society can be cruel to anyone who is different, especially if that kid also has the temerity to be themselves. Celebrate them for who they are. As the new school year gets under way, we’d be mindful to remember that and meet the kids where they are instead of where you expect them to be.