A candid shot of a dad walking with his daughter in Kowloon Park, Hong Kong. She kept trying to dance away from him, so he had to take her hand and play along.

One of the most profound things I have ever heard has no words. It is the father holding his daughter’s hand while walking through Kowloon Park. It is the elderly husband and wife walking arm-in-arm along the promenade. It is the friend pushing his friend in wheelchair. It is the mother and father playing a silly, made up game with their child on the MTR. It is the man who gives the homeless man four takeaway packages outside the 7-Eleven. It is the mother holding her son’s hand to help him up the stairs to Big Buddha. It is the sound of love and it is there if you take the time to look..

Paul and I were among the first visitors traveling to the Po Lin Monastery and the Tian Tan (Altar of Heaven) Big Buddha statue on a sunny Saturday morning. We traveled along the MTR and then in a Crystal Cabin cable car with a glass bottom, to take us to our destination.

Everyone participates in a quiet reverence on the journey. I suspect they came early for the same reasons we did – a desire to feel what this place is like when only the monks are here and a respect for what was built here more than a century ago.

The natural breeze cools us in the cable car as we silently wind our way up toward Lantau Peak. The Po Lin Monastery and the Buddha live in its shadow. We travel over water that flows in and out of the South China Sea. The water is green and, from on high, appears to undulate slowly.

You can hear the cicadas. They are somewhere on the ground below. I think of the katydids back home in New York. People are irritated by the sound, but it is a gentle, albeit noisy, reminder of home.

The breeze rustles the leaves on the trees below. Above the canopy, the sounds of birds spread through the air.

A Black Kite sails to and fro, eventually resting on a tree and disappears from view. The cable car continues to move silently through the air as we “fly” through the air. Just before we stop, cattle are seen resting in a nearby field.

Once on the ground again, we pass through Ngong Ping village. It is only beginning to bustle with activity. We have arrived before the shops are open. Our goal – to climb the 268 steps to the Buddha.

Elusive red dragonflies flit in front of us before rising above our heads and zipping along to do dragonfly things. They never rest. Views of them are fleeting. The shutter of my Nikon D7000 is useless to capture this tiny life. It is more fulfilling to simply watch the red dragonfly glide through the humid air.

Red and black butterflies pass in and out of the spaces between the leaves of the trees that line the path to the Buddha. They chase one another up and down the stairs, occasionally passing in front of homo sapiens on their journey upward. I lean back away from a pair that has flown too close to my face and smile. They are like little children at play, unaware of their surroundings as they participate in the joy of their flight.

About halfway up the stairs, I must move to the left side of the stairs. A lady is proceeding up five stairs at a time, then pausing to pray. Several steps ahead of her, a monk dressed in brown is also praying. Anyone who was speaking on the way up the steps ceases their words. It’s an automatic reaction. Though our mutterings were already quiet, the instinct to not disturb the faithful has kicked in.

The Po Lin Monastery can be seen in the background while three of “The Offering of the Six Devas,” Buddhistic statues praising and making offerings to the Tian Tan Buddha are in the foreground.

The wind at the base of the Buddha increases, whipping through my hair. It’s evident I will have windburn today, but I do not seek shelter. I rest my arms on the edge of a stone railing and take in the view below.

To say people look like ants is a cliche, but it is true. From above, it is evident throngs of people are arriving. The Po Lin Monastery stands out from the surrounding trees. Its reddish-tan roof is in distinct contrast to the lush green that surrounds it.

If one has patience, a photograph of the Po Lin Monastery entrance can be taken without people in it.

At the monastery, the smell of incense pervades the air. Worshipers gather around many stands to place incense sticks, large and small.

The faithful are in nearly every room the public is allowed to enter. When they speak, it is in whispers. Those of us who are not here to worship gently tug at one another’s shirt sleeves and point instead of vocalizing what we want our compatriots to see.

The monastery has signs in places it asks you to not take pictures. The Grand Hall of the Ten Thousand Buddhas is one such room. Five large, gold statues of the Dhyani Buddhas – Amoghasiddhi, Amitabha, Vairocana, Ratnasambhava, and Aksobya – are the centerpiece of the room.

Gold is everywhere. It is on the pillars and on each of the small Buddhas on the wall that make up the rest of the room. It is on the ceiling where gold is interspersed with blues and reds.

Those who are speaking in whispers fall silent as they enter the room. Is it the awe of so much gold in one place? Is it reverence? Respect?

In any other place, so much gold would appear to be gaudy, but here it seems more illuminating. Coins drop into a donation box. The clinking of metal disrupts the peacefulness of birds chirping in the nearby trees. The woman whose coins disturbed the near silence puts her hands up and quickly bows her head. Without saying a word, she has apologized to the five of us in the room.

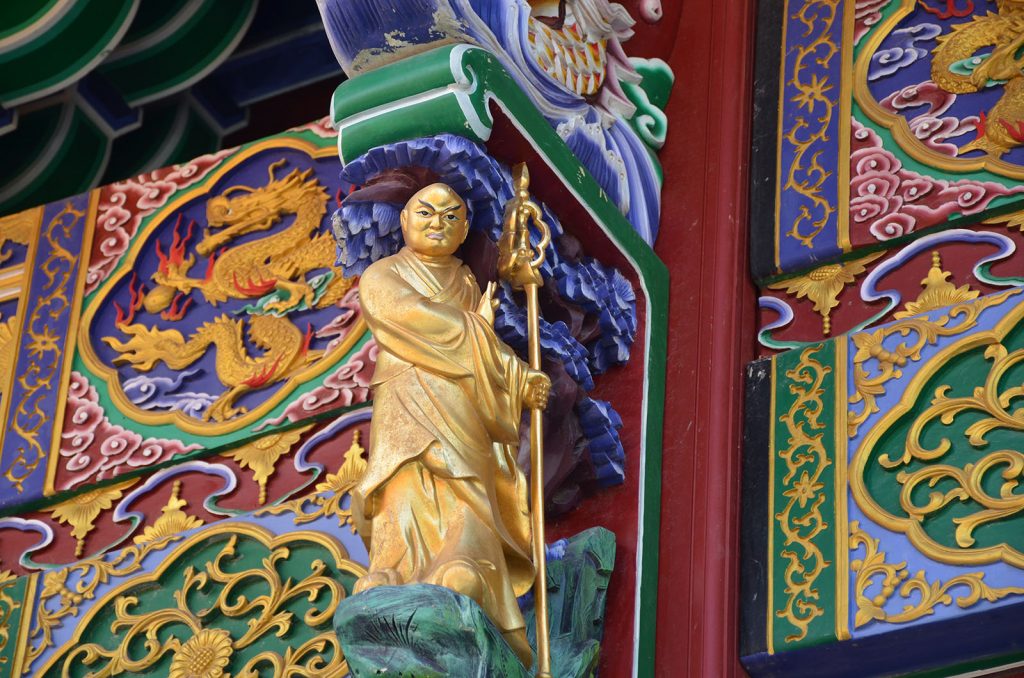

Outside, and on the exterior of the monastery are blues, greens, purples, whites, reds, and golds dancing and intermingling in intricate designs. As I stare up and trace the patterns with my eyes, a gentle breeze cools my face and shifts my hair back away from my face. The wind is a welcome touch on an overly humid day.

As we walk toward the trail that leads to the Wisdom Path, I watch and take photographs of what looks to be a garter snake. Others stopped as well. Instead of screaming at the sight of a tiny snake, we watched it as it traveled along its way.

A small, thin snake winds its way along the side walk about fifty feet before the entrance to the Wisdom Path on Lantau Island in Hong Kong.

It weaved in and out of the sewer grate along the side of the road, dipping in and out of sight only to have its blueberry-colored head and large, dark eyes emerge again. The snake’s black, yellow, red, and green body seemed to shimmer as it moved from shade to sun, back to shade again.

The snake stopped at the edge of the metal grate and climbed up the stone edge of the side walk, then moved swiftly over another grate on top of the side walk. There was no need to fear it because it was different than us. It, too, was just looking to find its way in life.

A bee makes a stop on a flower along the Wisdom Path in a symbiotic relationship that was developed over millions of years of evolution.

The trail to the Wisdom Path is filled with life. It is not a strenuous physical walk, but one is mindful of their surroundings and their role along the way. If you tread lightly, you can almost make out the buzzing of a bee gathering nectar and pollen from a purple flower in the woods along the trail. It takes what it needs before moving on.

Strolling along the trail, there are other signs of life, mostly small creatures who share this planet with us. Visitors continue on their way, unaware of what is moving and living among us.

The Wisdom Path is arranged in a ∞ pattern to represent infinity. The 38 wooden steles contain verses from the Heart Sutra, one of the best-known prayers that is revered by Confucians, Buddhists, and Taoists. Written in the Chinese version of the prayer and based on the calligraphy of Professor Jao Tsung-I, the stele are meant to evoke memories of the zujian, or bamboo tiles, that were used for writing in ancient times.

The column at the highest point of the hill is blank, representing sunyata, or emptiness, a central theme of the Heart Sutra. The emptiness is not what we normally think of when we hear the word. It teaches that everything is dependent on something else.

The prayer is a declaration of the perfection of wisdom. Once we learn the wisdom of the “emptiness,” we realize that all physical and mental events are in a constant state of change and we can change anything by modifying the conditions.

With this understanding, it is said we can be free from mental obstructions and attain perfect harmony. The Heart Sutra is a visceral attack on everything we know. It tears down how we think and how we see the world. It will quiet a restless heart. It is the starting point for how each of us contemplate our existence.

And it is so much more than that.

You can walk the figure eight path of the Wisdom Path and contemplate any number of things, including the meaning of the Heart Sutra. The natural beauty and the peacefulness is enough to calm and soothe any anxious and uneasy mind.

The journey back along the trail that took us to the Wisdom Path revealed more life along the way. A shimmering, golden- and rust-colored, elongated bug walked along the dirt, shifting its body over twigs, smashed blue-colored berries, and rocks. As it climbed over one stone, the bug stumbled. It was off-balance. It flipped on its back.

It grabbed onto a nearby twig and wrapped its legs around the twig, but it couldn’t shift its weight to turn back over. It ceased all movement. I placed my camera on the path, reached down, and gently picked up the twig. The bug tightened its grip on the twig. Slowly, I turned the twig. When the bug was upright, I placed it back onto the ground. The bug scurried on its way to wherever it had been going when the mishap occurred.

On our way out of Ngong Ping village, we stopped to put our wishes with everyone else’s. It doesn’t mean anything, but writing things down has a way of making you feel better about whatever words you just made. It helps to ease the burdens we often carry with us. We climbed aboard our cable car and said goodbye to the giant Buddha from the sky.

The Buddha’s right hand is raised, representing the removal of affliction, while the left rests open on his lap in a gesture of generosity.

The sounds of love clangor at the top of Lantau Island. The gentle breeze cooling you on a hot day, small acts of kindness, and time for contemplation allow you to see how we are all interconnected. Our love, empathy, and compassion for each other and the living, breathing things around us make for a better world. We need not ever make a sound to speak loudly to that truth.

Judy

This journey you are taking is so foreign to our lives. through your eyes I see the feeling of peace and comfort and understanding that the Chinese culture strives for in the midst of a very crowded and busy world.